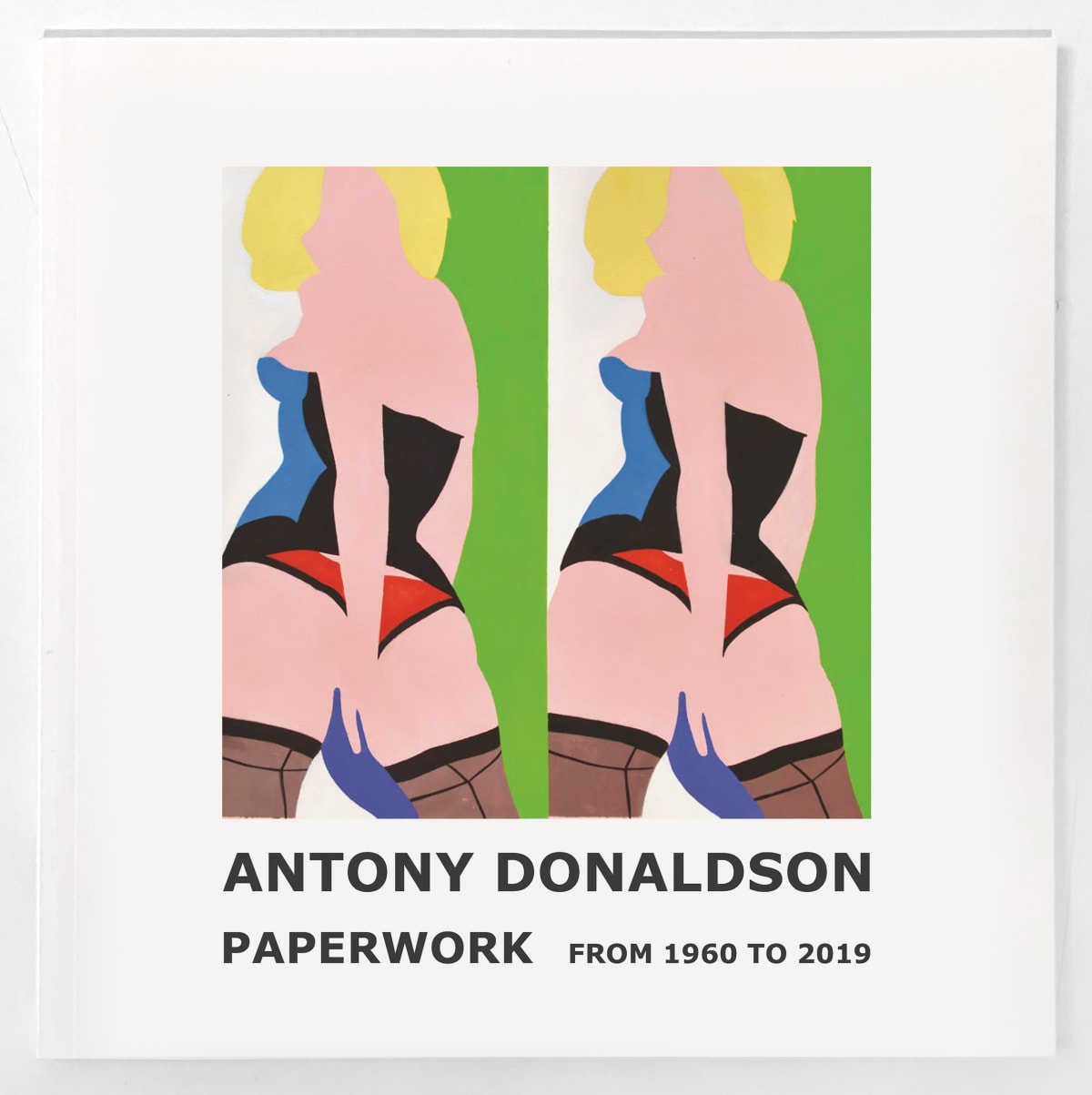

ANTONY DONALDSON: PAPERWORK FROM 1960 TO 2019

‘I liked Tony immediately because he’s smart and cultured, but he speaks his mind in a very direct way, and that’s unusual for the English,’ the artist Joe Goode has said of his friend of over 50 years. This show of drawings and prints, which covers Antony Donaldson’s career since he was a student at the Slade to the present, confirms that Joe Goode’s long-held opinion of his friend’s character is no less true of his art.

Donaldson’s art is indeed smart - it questions ceaselessly and scrupulously subverts clichés. It is cultured, in the breadth of its reference, and it is erotic to the nth degree of refinement, which is indeed most un-English. Pre-1960 there wasn’t much English art that dwelt on female sensuality. Donaldson was in the vanguard of that change and as the ultimate authority Marco Livingstone has written (Antony Donaldson Of Memory and Oblivion, The Mayor Gallery, 2015), far from objectifying women in a male-dominated society his female images, early and late, while ‘sexually alluring’ also ‘exude a certain innocence’. There are 48 works on paper and all but eight of them feature alluringly youthful women. Other subjects – racing cars, planes, searchlight beams - are no less sensually described.

Donaldson was born in 1939. His grandmother went three times to Buckingham Palace in World War II to receive DSOs from George VI on behalf of her three fighter-pilot sons. Donaldson’s father was killed in action in 1940 adding a proud memorial note to the two World War II aeroplanes in this selection, derived from photographs Donaldson took at the National Championships in Reno, Nevada, in 2008. ‘Six World War II planes climbed to about 8,000 feet and dived towards the start line where I was. The race director said over the radio to the pilots, ‘Gentlemen, Fly Low, Fly Fast and Turn Left’, straight at me.’

The earliest drawing, Lilies, is from the Slade years where Donaldson won the top degree. The reward, a postgraduate scholarship, meant he had a further year of paid study. The end of British national service coincided, as Donaldson says, in London and beyond with an ‘amazing explosion which transformed cinema, writing, poetry and art in the years he was at art school’. The contraceptive pill followed, creating no less of a transformation in social mores. In 1960 he and the beautiful Patricia Marks were married. She has been his muse ever since.

In 1963 he had his first solo show at Alex Gregory-Hood’s new Rowan Gallery. The following year Donaldson was chosen for the landmark New Generation exhibition at the Whitechapel Gallery which included Allen Jones and David Hockney. Allen Jones has commented that although Donaldson had a ‘maverick’ reputation ‘the Tate bought a picture from him before they bought one from anyone else!’ ‘His was a precocious talent and known to me as the only pop inspired not to have been at the RCA.’

The 1960s introduced silkscreen-printing to fine art and quick-drying, water based, acrylic paint – Early No 84 an example. The decade climaxed for Donaldson and his now family of three with a 2-year Harkness Foundation Fellowship to the USA. He and his family arrived (in L.A.) and were duly amazed by the film-premiere searchlights, neon-accentuated Art Deco cinema facades, customised cars and subtle paint effects attainable with spray-guns and airbrushes. A number of the works in the show originate from his friendship with the late Alain Bernardin, founder of the Parisian strip-club the Crazy Horse Saloon.

Latterly Donaldson took up sculpture in a variety of media, including carving in marble. His most famous piece is the giant Buddha-like head of Alfred Hitchcock, Master of Suspense. It commands the courtyard of the £38 million revamp of Gainsborough Film Studios. Two arresting watercolours, Master of Suspense, demonstrate the amount of preparatory work there is for such major sculptural commissions. They add to the abundant ways Antony Donaldson disarms the eye for the minority who get the ‘why’ of a picture, as well as satisfying the pleasure of those whose first demand is for the ‘what’ of representation. They also show an artist who has never lost his youthful exuberance or his maverick and international inclination.

- Extract of The Disarming Eye by John McEwen, written on the occasion of this exhibition