Julian Stanczak: Beyond the Mirror

-

JULIAN STANCZAK, Green Light, 1973

JULIAN STANCZAK, Green Light, 1973 -

Julian StanczakMediterranean, 1971-72Acrylic on canvas127 x 178 cm

Julian StanczakMediterranean, 1971-72Acrylic on canvas127 x 178 cm

50 x 70 1/8 inches -

Julian StanczakFrigid Sequence, 1978Acrylic on canvas153 x 153 cm

Julian StanczakFrigid Sequence, 1978Acrylic on canvas153 x 153 cm

60 1/4 x 60 1/4 inches -

Julian StanczakCentral Meeting White, 2008Acrylic on panel61 x 61 cm

Julian StanczakCentral Meeting White, 2008Acrylic on panel61 x 61 cm

24 x 24 inches -

JULIAN STANCZAK, Suspended, 1990

JULIAN STANCZAK, Suspended, 1990 -

Julian StanczakCentral Meeting, 2008Acrylic on panel61 x 61 cm

Julian StanczakCentral Meeting, 2008Acrylic on panel61 x 61 cm

24 x 24 inches -

Julian StanczakSpring Fold, 1973Acrylic on canvas81 x 188 cm

Julian StanczakSpring Fold, 1973Acrylic on canvas81 x 188 cm

31 7/8 x 74 inches -

JULIAN STANCZAK, Accumulating Warm, 2002

JULIAN STANCZAK, Accumulating Warm, 2002 -

Julian StanczakWindows to the Past, Light Gray, 2000Acrylic on panel40.6 x 40.6 cm

Julian StanczakWindows to the Past, Light Gray, 2000Acrylic on panel40.6 x 40.6 cm

16 x 16 inches -

Julian StanczakUnveiling in Blue, 1972Acrylic on canvas71 x 71 cm

Julian StanczakUnveiling in Blue, 1972Acrylic on canvas71 x 71 cm

28 x 28 inches -

Julian StanczakStructural-Cobalt, 2012Acrylic on panel61 x 61.4 cm

Julian StanczakStructural-Cobalt, 2012Acrylic on panel61 x 61.4 cm

24 x 24 1/8 inches -

Julian StanczakTwist and the Rain, Gray, 1975Acrylic on canvas71 x 61 cm

Julian StanczakTwist and the Rain, Gray, 1975Acrylic on canvas71 x 61 cm

28 x 24 inches -

JULIAN STANCZAK, Winged Squares, 1973

JULIAN STANCZAK, Winged Squares, 1973 -

JULIAN STANCZAK, Rejoined Warm, 1973

JULIAN STANCZAK, Rejoined Warm, 1973 -

JULIAN STANCZAK, Opposing Temperature I and II, 2003

JULIAN STANCZAK, Opposing Temperature I and II, 2003

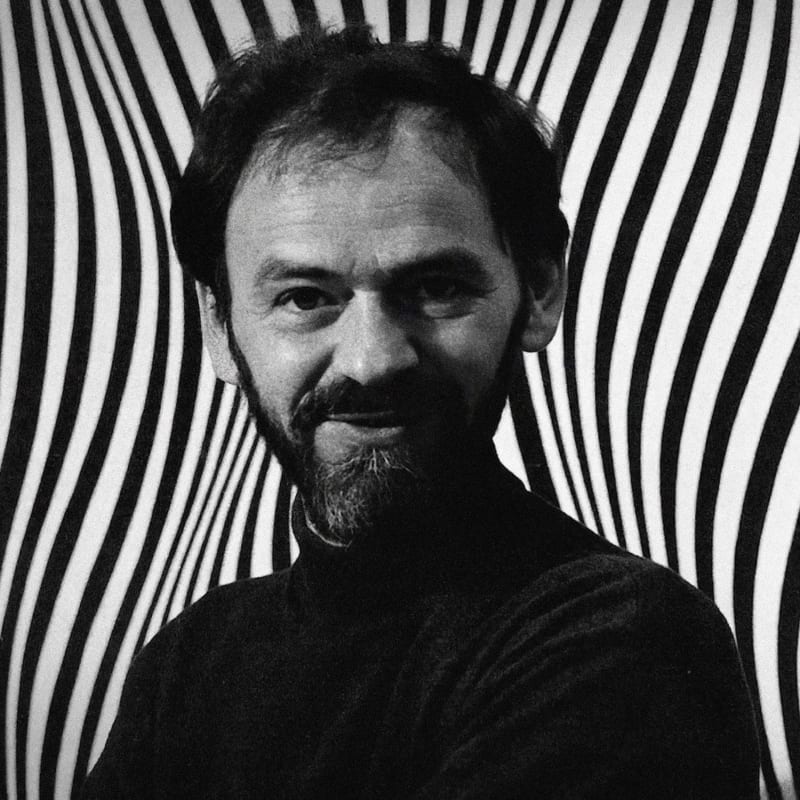

A leading artist of Op Art, Julian Stanczak (b. 1928 Borownica, Poland – d. 2017 Ohio, United States) created from the 1960s a dynamic and joyous oeuvre. The term Op Art itself was coined by Time magazine after his first major show, Julian Stanczak: Optical Paintings, held at the Martha Jackson Gallery in New York in 1964 where his paintings, full of colour and optimism, gave nothing of his traumatic childhood.

In 1940 Stanczak and his family were forced into a Siberian labour camp, where he permanently lost the use of his right arm. In 1942, aged thirteen, Stanczak escaped to join the Polish army-in-exile in Persia. After deserting from the army, he spent his teenage years in a Polish refugee camp in Uganda. It was there, in Africa, that he learned to write and paint with his left-hand, he was profoundly affected by the African light, the intensely coloured sunsets and what he called “the immense visual energy” of the fauna and flora and the colourful patterned Ugandan textiles worn by the local women.

In 1950 the family relocated to Cleveland USA via London, England. He studied at the Cleveland Institute of Art and later trained under Josef Albers at Yale University where he received his Master of Fine Arts in 1956 and became a US citizen in 1957. Influenced by his teacher Josef Albers, Russian Suprematism and Constructivism, Stanczak wanted to achieve an extreme sensory experience for the viewer. His abstract compositions are full of vibrating colours and optical illusion. Shapes pulsate, colours glow, and vertical lines dance across his intensely energetic canvases.

Stanczak was interested in the emotions that colour can evoke, which are personal and unique to each viewer, hoping to provide an ultimately uplifting experience. He once said that his style was an attempt to forget about his war traumas. “I did not want to be bombarded daily by the past,” he said. “I looked for anonymity of actions through nonreferential abstract art.”

In 1965 Stanczak pushed this further by using tape to control the application of paint, distancing himself from the canvas and removing any evidence of his own hand. Stanczak felt that this way the viewer is completely free to impose their own meaning and emotional response to the work, to reflect inwardly and see themselves in the painting, much like a mirror.

Stanczak took part to the Museum of Modern Art's seminal 1965 exhibition The Responsive Eye. In 60 years of painting, Stanczak has proven to be a leading colourist of the 20th Century. His paintings are included in numerous public and private collections, including more than 100 museums.