Robert Scull

I was just 21 when I first met Bob at Parke Bernet (where I was working) in the spring of 1970, in front of Warhol’s Big Torn Campbell’s Soup Can (Vegetable Beef) that Peter Brant was selling. There was a rumour at the time that Scull had sold his collection to Heiner Freidrich. So in conversation with this man I said that it was a tragedy that the Scull collection would be lost to the USA to which he replied, “That’s not actually true and I should know- because I am Scull!” and we became great friends from then on.

Bob really loved art and had a real understanding and passion for it. He wasn’t a speculator but a genuine collector, who was prepared to put his money where his mouth was, why else would he have financed some of those huge Land Pieces by Michael Heizer and Walter de Maria? He had a real eye, and even with artists whose work had fallen out of fashion you could be sure he had their best works. Some people have called him vulgar and crass, he wasn’t at all and in reality they were probably just jealous of him.

I would like to put the record straight about the sale of the Brant Soup Can as almost every version I have read or heard about is complete rubbish. I have never understood why nobody has ever bothered to ask me as I was the one that put the sale together. Peter bought this one from Hanford Yang in 1969 and a little time later Leo Castelli offered him two Warhols belonging to Bob Rowan for $90,000 - Big Campbell’s Soup Can 19¢ (Beef Noodle) and Lavender Disaster (both now in the Menil Collection in Houston). Peter couldn’t afford to keep both Soup Cans and because Leo had told him that the 19¢ was the more important work (maybe because he didn’t want to lose the deal) Peter decided to sell Torn Label as he had been offered over $50,000 for it by both Leo Castelli and Bruno Bischofberger. When he contacted me about selling it at auction it was the first time that I had met him, naturally I was delighted to have such an important work in my first sale. The slightly unusual but by no means unknown part of the deal was that Peter negotiated a fixed fee. The painting went on to sell for $60,000 to the Zurich Kunstmuseum.

In the spring of 1973 soon after I had left Parke Bernet, Bob had decided to sell 50 works from his collection with a guarantee of $2,000,000 but suggested that they should have me advise them on the sale. They agreed to this and offered to pay me $18,000 plus all expenses for a week’s work which was 50% more than I was paid the whole of 1972! Immediately after the famous Scull Sale Bob offered me 15 works from his collection for $1,000,000: five Rosenquists, four Johns, three Warhols, two Wesselmanns and a Twombly. Sadly I couldn’t find anybody to finance it, yet over the years I did sell all of the Rosenquists, two of the Johns, both Wesselmanns, one Warhol and the Twombly for rather more.

James Rosenquist, Doorstop, 1963, oil on canvas, 60 1/8 x 83 7/8 x 16 3/4 inches (152.6 x 213 x 42.5 cm), Museum of Modern Art, New York

In about 1978, Bob wanted to sell me three works: Rosenquist’s 4 Guys, Twombly’s Settebello and Wesselmann’s Great American Nude no. 30. I suggested a price to which he replied, “You must think I’ve still got hayseed in my hair, try again”. So I upped my offer and everyone was happy. Shortly afterwards Roberto Shorto, who was then Heine Thyssen’s brother-in-law, told me that they wanted to buy a Jasper Johns. Bob and I decided to offer them False Start for $375,000. Everything seemed fine and I arranged to meet Roberto in New York in order to see it and finalise the deal. When I went to rendezvous with Roberto in New York, he never turned up; Madrid’s loss and Chicago’s gain.

Bob consigned us a number of Rosenquists as well as Johns’ Double Flag which I failed to sell and Warhol’s Big Torn Campbell’s Soup Can (Pepper Pot) which I sold to a great friend along with Rosenquist’s Doorstop. When Kynaston McShine saw the show he was very disappointed that Doorstop had already been sold, so when I was asked to resell it many years later I immediately called Kynaston who promptly bought it for the MOMA in New York. As for the Soup Can, years later I was asked to resell it and it went to Francois Pinault who later sold it to Esther Grether in Basle.

Yves Klein, Le Rose du bleu, 1960, dry pigment in synthetic resin, natural sponges and pebbles on board, 78 3/8 x 60 x 6 3/8 inches (199 x 153 x 16 cm), Private Collection

In early 1983, Francois de Menil wanted to sell his collection of four works by Yves Klein - a large Blue Sponge relief (RE11), a Gold Sponge Relief (RE47 II), a large Fire Painting (FC27) and the pink sponge Rose de Bleu (RE22). I knew that Magnus Lindholm loved Klein’s work and this would be a unique opportunity for him. We arranged to go and see them together in Francois’s office and he landed up buying the group for $425,000. Many years later Magnus started selling them off at auction where they sold for over $76,000,000, including the then world record of just over $36,500,000 for the Rose de Bleu.

So when a friend of mine, who had bought the Johns’s Target at the Scull sale in 1973 and gone on to to loan it to the Art Institute of Chicago, asked me to sell it for him for a $1,000,000 net to him, I immediately offered it to Magnus. As he liked the look of it, we agreed that we would go together and take a look at it. We fixed a date and agreed to take the 9 am flight, however we forgot to say which airline and which airport and as it was before mobile telephones it was impossible to reach each other. Luckily we both plumped for the same flight and the deal was done. Magnus continued lending it to the Art Institute for some time. It is now back hanging in the Art Institute as a gift of Stefan Edlis and Gael Neeson. The last time I was in the Art Institute, I saw the first painting I sold for more than $1,000,000 (False Start) facing the third one (Target).

Jasper Johns, Target, 1961, encaustic and newspaper on canvas, 66 x 66 inches (167.6 x 167.6 cm), Art Institute of Chicago

Edward James Foundation

I had been at a Sotheby’s sale where The Edward James Foundation was selling a number of paintings. One of them, a Giorgio di Chirico, sold for about £600,000, which was way over their estimate of about £150,000. The underbidder was an Italian/South African who was seated with his bodyguards and a member of Sotheby’s staff who did the bidding for him. The next day I was talking with Christopher Gibbs, who was one of the Foundation’s trustees, when he mentioned the previous day’s sale where apparently the Sotheby’s expert had told him that there had been a misunderstanding with the buyer’s bidding instructions and that in hindsight it was clear he had stopped bidding at £150,000 and as they had no idea who the underbidder was they had agreed to sell it to the buyer for around £150,000. I was able to tell Chrissie that this was complete nonsense, so armed with that information the Foundation went back to Sotheby’s who, after some protestation, agreed to pay the full amount as they were obviously too nervous to contact the underbidder in case he twigged he had been run up for a few £100,000s. Ira Spanierman sometimes used rather an unusual bidding technique, which involved whether his flies were open or not, that required John Marion, Parke Bernet’s chief auctioneer, having to peer into Ira’s crotch throughout the auction.

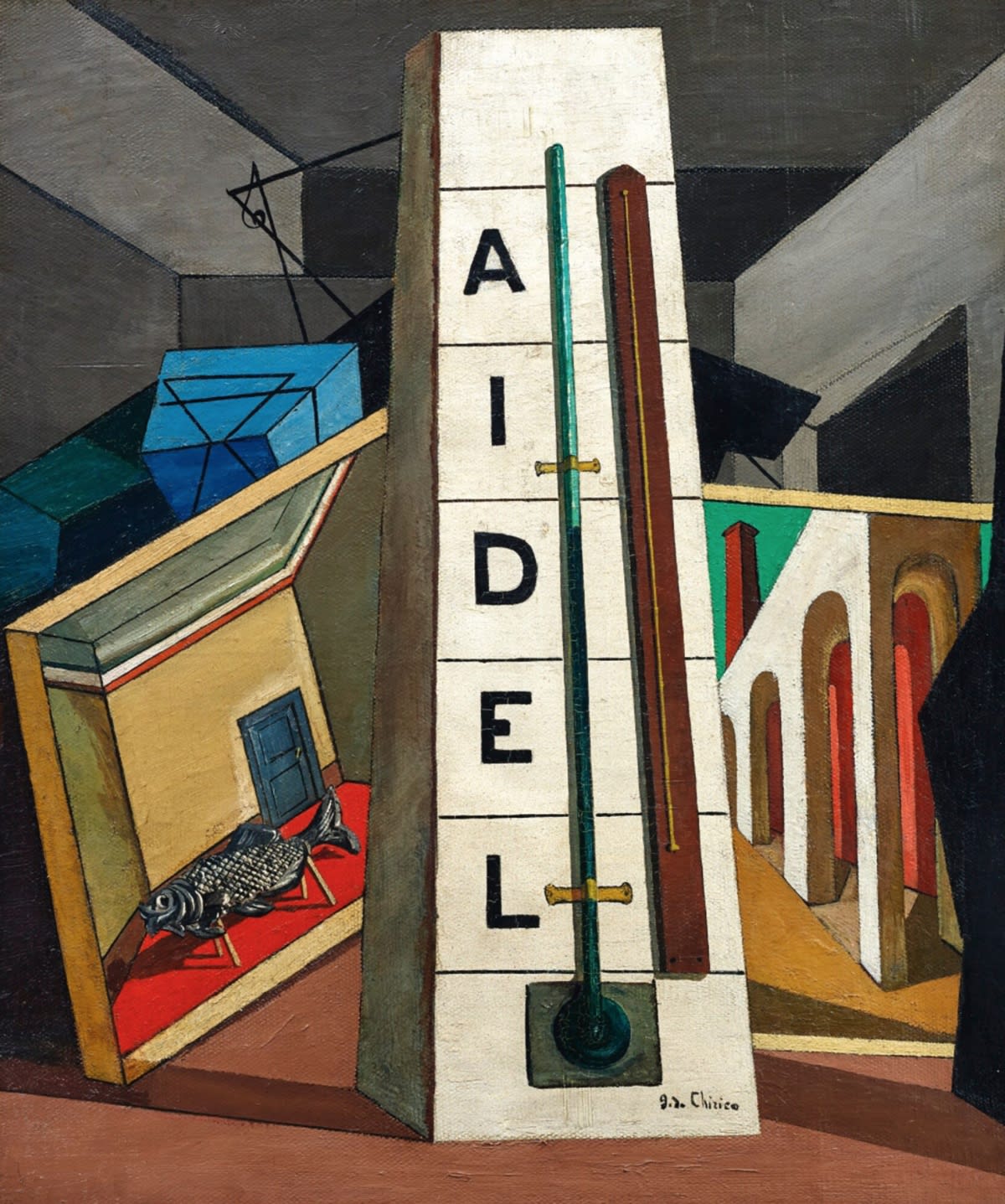

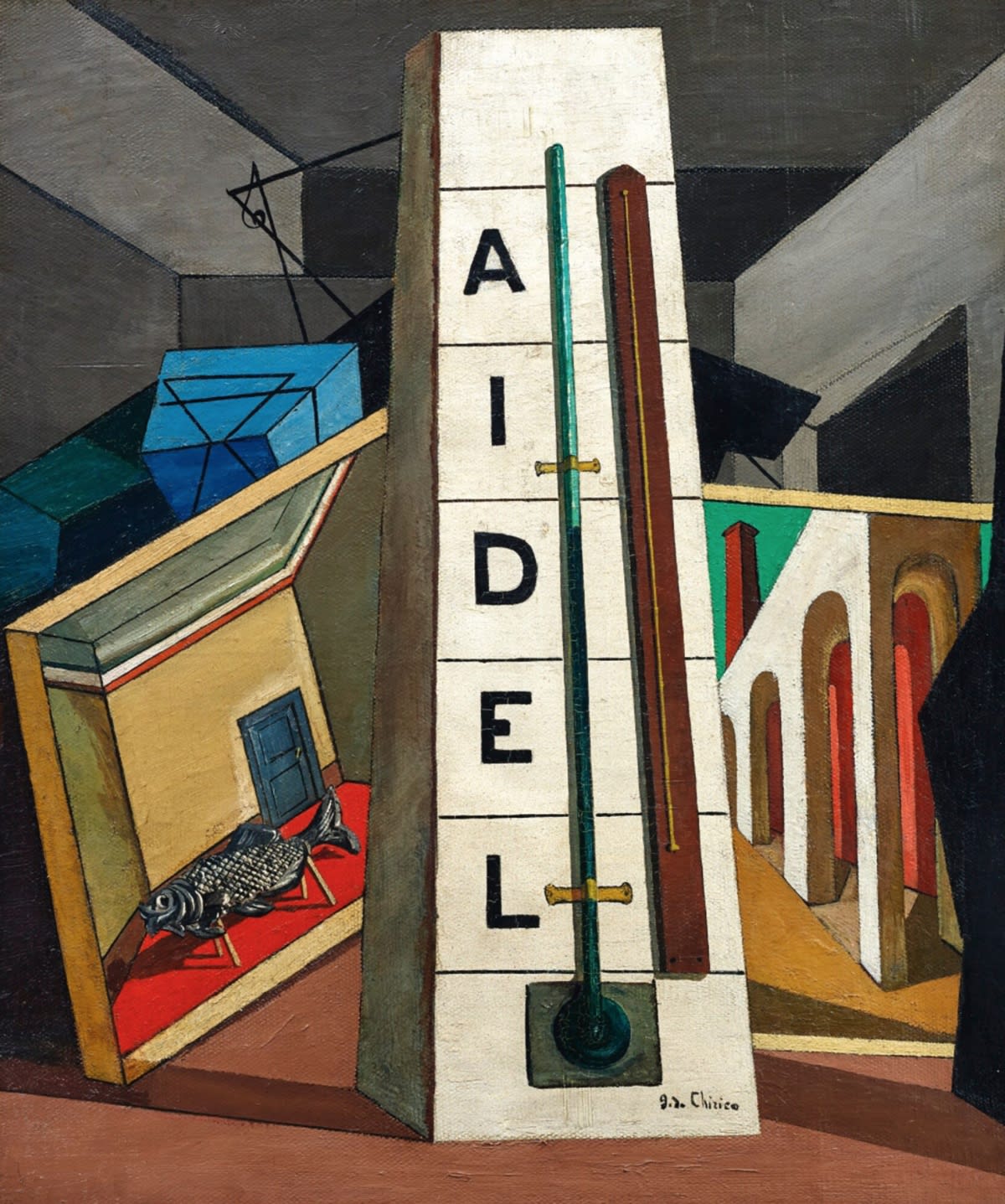

Giorgio di Chirico, Il Sogno di Tobia (The Dream of Tobias), 1917, oil in canvas, 23 1/4 x 19 1/4 inches (59 x 49 cm), Private Collection

As a result of this - I suppose by way of a thank you - we became one of the Foundation’s unofficial dealers. The first work we were given to sell was di Chirico’s Dream of Tobias. The painting was in his retrospective at the MOMA and therefore easily viewed, making it very easy to sell through Mario Tazzoli And Massimo Martino. However that wasn’t the end of the story - I assumed, as at the time of the sale the painting was on exhibition in New York, that it had all the necessary export documents. Apparently this wasn’t the case; it was on a temporary license solely for the exhibition. After a lot of toing and froing and threats of large fines, it was agreed that I had made a genuine mistake and their client got his painting.

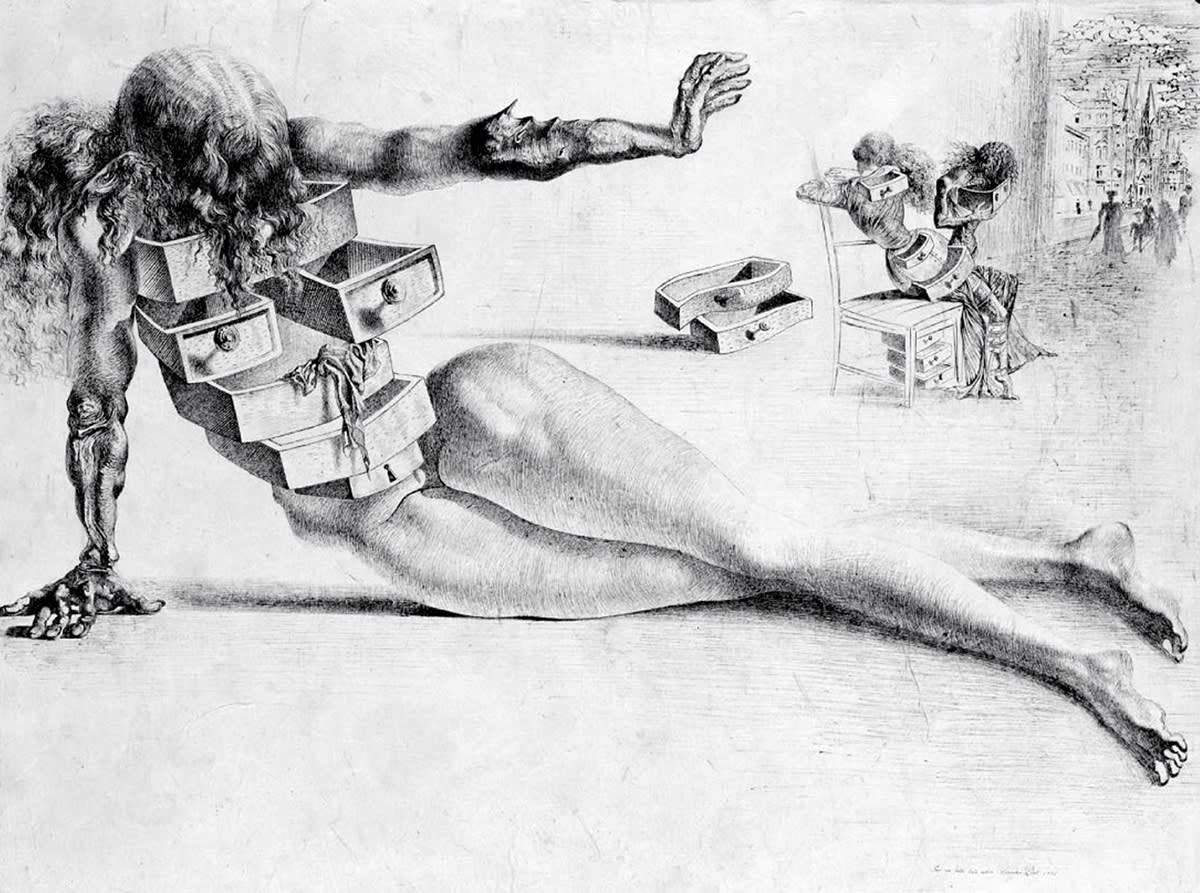

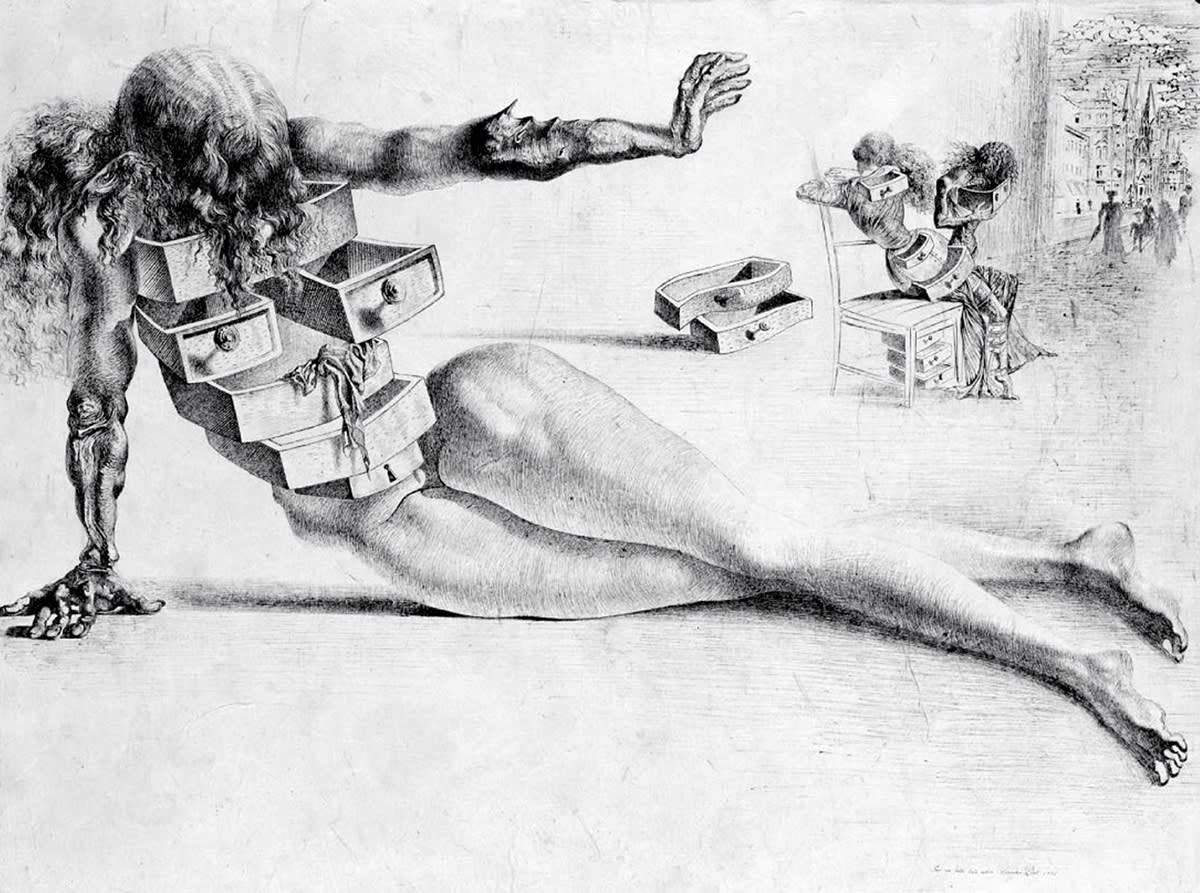

The next involvement with the Foundation was the exhibition of 50 works on paper by Dali that we did in conjunction with Robert Fraser. Edward James had been Dali’s sponsor in the mid and late 1930’s and therefore had at one time an enormous and extremely important collection of his work. Ed and Lindy Bergman from Chicago were in London just before the show opened and I showed them all the works where they expressed an interest in City of Drawers, Portrait Imaginaire de Lautremont a 19 ans and Formation des Montres. Unfortunately we inadvertently sold the City of Drawers to somebody else and thankfully they were very gracious about it and just bought the two drawings which are now in the Art Institute of Chicago and an oil painting by Jim Nutt.

Salvador Dali, The City of Drawers - Study for the 'Anthropomorphic Cabinet', 1936, pen and ink on copper gravure paper, 12 1/2 x 16 3/8 inches (32 x 41.5 cm), Private Collection

June 11, 2020