Sir Roland Penrose

Roland died on St. George’s Day (23 April) exactly 77 years after his late wife’s - Lee Miller - birth. My father met him in Cassis in 1923 and they remained friends for 50 years (Roland gave the address at my father’s funeral). He was from a Quaker banking family and was without a doubt one of the great patrons of Modern Art in England in the 20th century. Although he is best known as a collector and - being a close friend - as Picasso’s biographer, he really wanted to be known as an artist first. My father gave him an exhibition in 1939 where they employed a ‘sandwich board man’ to sit in the window during gallery hours. Unfortunately some old busybody went and complained to the police about cruelty to tramps, so the man had to leave. Needless to say he was furious as he thought this was the best job he’d ever had: all the beer he wanted and being paid to sleep it off. I gave Roland a couple of shows: one of recent collages in 1983 and with Timothy Baum in 1990 we did a show ‘Two Old Pals: Man Ray and Roland Penrose’.

In 1936, he co-curated the great ‘International Surrealist Exhibition’ and also was responsible for bringing Picasso’s Guernica for exhibition in England. In 1947, he co-founded and co-funded the ICA, which during the 1950’s was the true centre of the contemporary art scene in London. In the 1960’s he organised the seminal exhibitions of Picasso and Miró at the Tate. In 1975, he setup the Elephant Trust with the proceeds of sale of Max Ernst’s ‘Celebes’ to the Tate. I had a collector in Chicago who was prepared to pay more than the Tate but Roland told me: “No I want it to go to the Tate and all the money is going to charity”. The Elephant Trust is still to this day one of the main English art charities.

Lee Miller, Man Ray and Roland Penrose, 1936 © Lee Miller Archive

Strangely the Tate’s bureaucracy nearly got in the way when Roland as co-curator of the great ‘Dada and Surrealism Revisited’ exhibition at the Hayward wanted to borrow Celebes. The Tate became very concerned about lending it, although the Hayward was probably nearer than their storage and in effect under the same ownership. After asking me to do the insurance valuation and some pressure from Roland they did agree to lend it. There was another Ernst painting the curators also desperately wanted for the show, which was Revolution by Night. It had been Roland’s and was bought by Agnelli. They were getting nowhere with the loan so I suggested that I contact my old Italian friend Mario Tazzoli. Mario was a childhood friend of Agnelli’s and he said that it shouldn’t be a problem, and it wasn’t – the painting was made available immediately and was subsequently bought by the Tate.

Pablo Picasso, Weeping Woman, 1937, oil on canvas, 24 x 19 1/2 inches (60.8 x 50 cm), Tate Modern

Picasso’s The Weeping Woman wasn’t the easiest picture to sell because we really did want it to go to the right place. I offered it first to the Tate and the Tate hummed and hawed. I offered it to the Museum of Modern Art and Bill Rubin came to see it. MOMA had just had to hand back Guernica to Spain following the death of Franco, and he was very off-hand about it. Extraordinary! We did everything we could. I always think paintings have a life and it’s important they should go to a proper home rather than just be sent out into the market place.

It was a very complex deal. Grey Gowrie, who had been the Minister of the Arts, was very helpful. It was complex because the painting belonged to Tony and not his late father’s estate. But when the sale to the Tate eventually went through one of the gossip columns reported it had been sold by the estate. The Inland Revenue notoriously use the gossip columns for information, so they went ‘Aha!’, because this would have meant more death duties for them. But Tony was absolutely clear it belonged to him. He and I had been at Port Regis prep school together and he told me: ‘I remember when I was given the picture because I was at Waterloo catching the train back to Semley Junction [the station for Port Regis] and my father said: “I’m giving you The Weeping Woman”.’ At the time Tony hadn’t thought this anything out of the ordinary because he assumed everyone had Picassos in their bedroom! In the end we managed to prove to the Inland Revenue that the picture was Tony’s and not the estate’s. It was a lesson to stay out of the gossip columns.

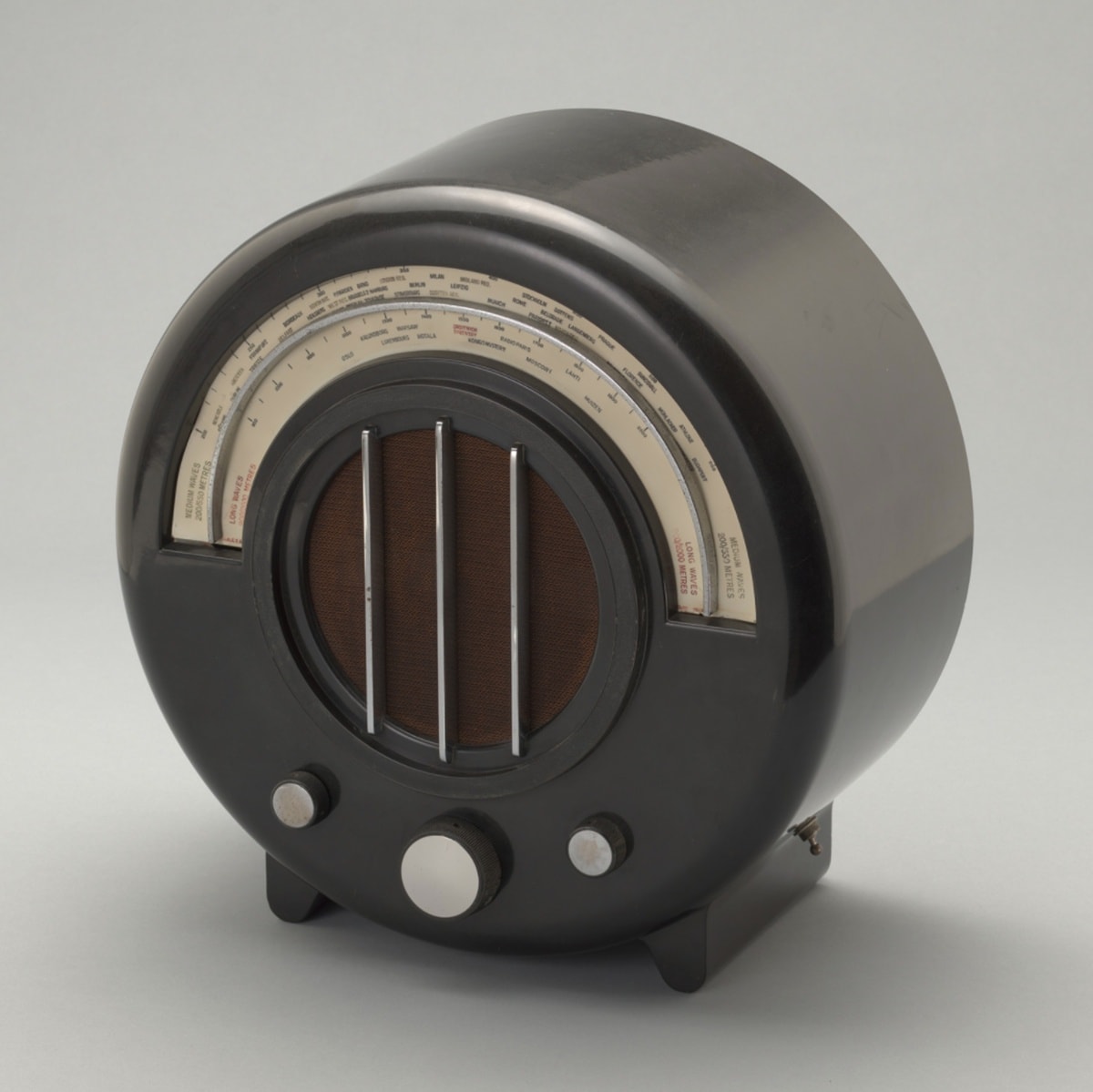

Ecko Wireless Radio - AD65, design by Wells Coates, Wolfsonian Miami Beach

Unit One

In May we commemorated the 50th anniversary of my father’s Unit One exhibition; in 1934 the Mayor Gallery had been its headquarters. We did this show with Mark Glazebrook, who wrote a brilliant essay about its origins. We managed to represent all the members but when it came to Wells Coates, the architect, the only way was by showing his Bakelite radios, which Andrew Murray managed to find at Alfie’s Market. This one, AD65, we sold through the Fine Art Society to Micky Wolfson for his Wolfsonian Museum in Miami Beach. The most awful thing happened when the Henry Moore Seated Figure, 1929 was stolen in broad daylight, which was no mean feat as it weighed a lot as since it was carved concrete and would have needed at least two people to carry it out. We had borrowed it from Henry and although it was found undamaged many years later it was sadly only after he had died.

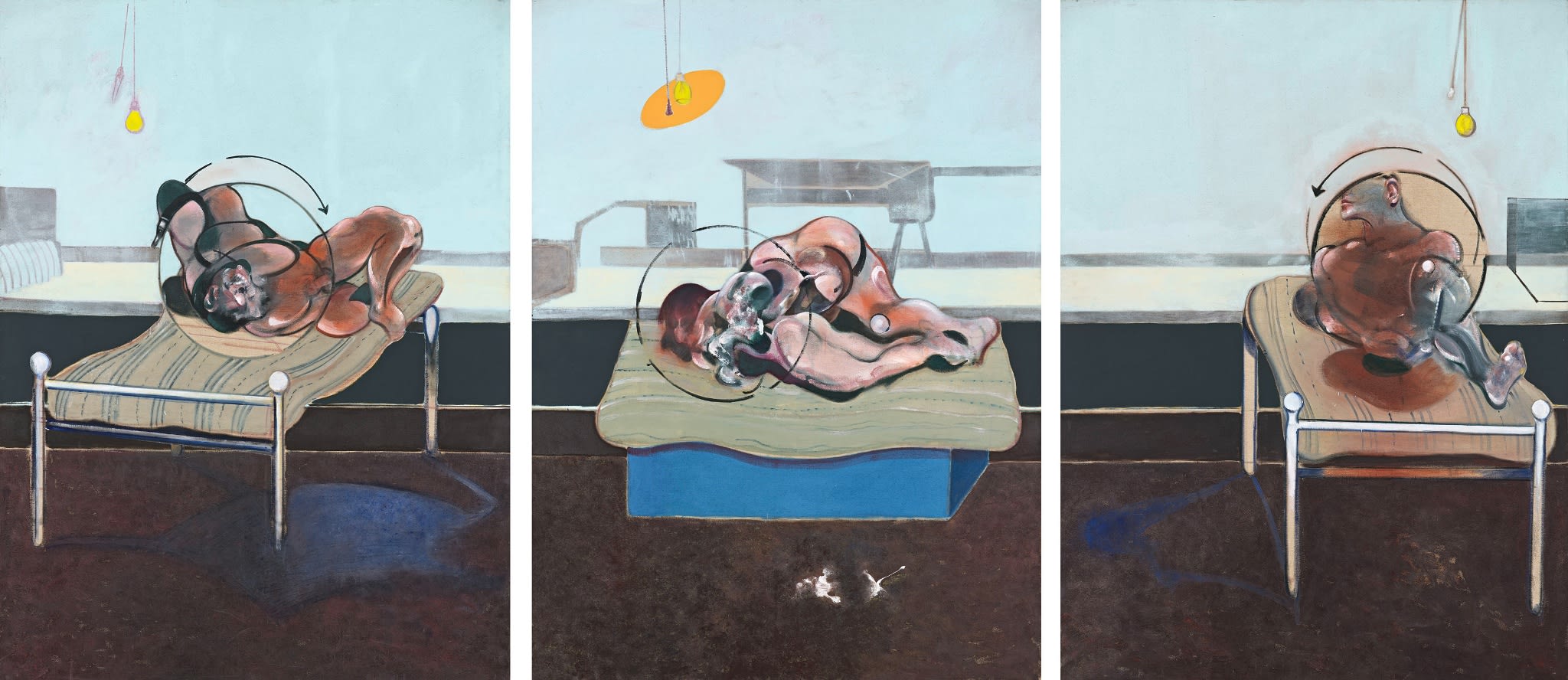

Francis Bacon, Three studies of figures on bed, 1972, oil and pastel on canvas, Triptych; each 78 x 58 inches (198 x 147.5 cm), Private Collection

A New Spirit in Painting

In Norman Rosenthal’s ground breaking show at the Royal Academy in 1981, it was the first time that late Picassos were put in perspective with Post Modernism. In the show there was a magnificent triptych Three Studies of Figures on Beds, 1972, by Francis Bacon that belonged to a Belgium friend of mine to whom I had sold some of the Pattern and Decoration work. In the late spring my friend asked me if I would like to sell it for him, as having recently moved he had absolutely nowhere to hang it. Of course I was delighted and sold it just before the summer for $620,000, which was probably a record at the time. About 10 years later the client I sold it to resold it for about $5,000,000 to Beyeler who bought it for Esther Grether.

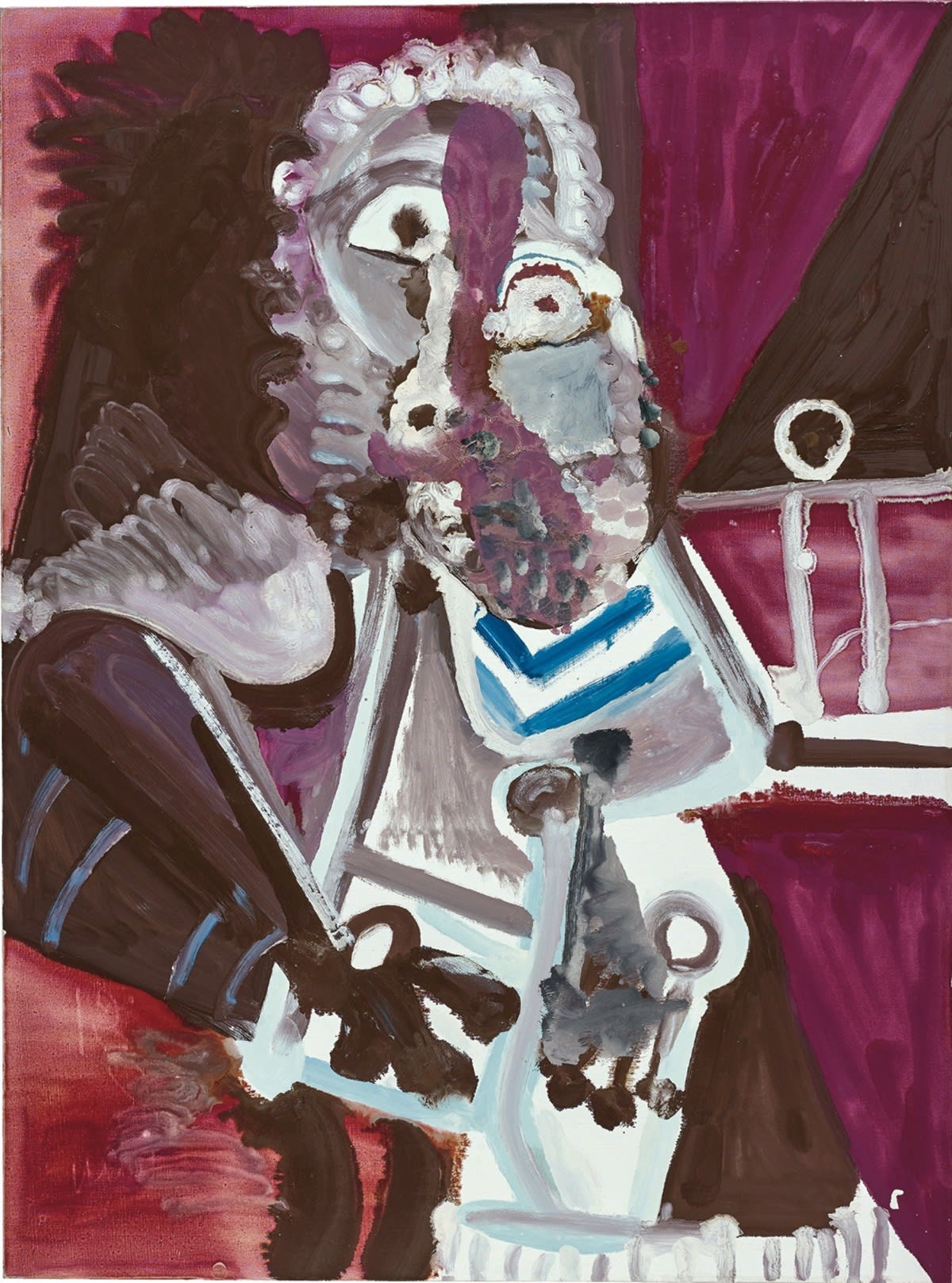

Pablo Picasso, Homme assis (Mardi gras), 1972, oil on canvas, 51 x 38 1/4 inches (129.5 x 97.2 cm), Private Collection

Summer Selection

In the show we had a late Picasso, Homme Assis (Mardi Gras), 1972, which I sold to Miles Fiterman for just over $100,000 (his estate went on to sell it for about $4,000,000). I had known Miles since 1970 and had sold him a number of works including a handful of Lichtensteins. This particular negotiation amused me as all through it he referred to the painting as a rather ordinary work but immediately after he bought it he wrote thanking me for selling him this masterpiece. Miles had been in the construction business and so when, in 1971, Gordon Locksley, the Minneapolis dealer, was giving Carl Andre a show and needed some blocks of cedar wood Gordon contacted Miles to see if he could supply them; which he did willingly. However I remember him telling me he was rather surprised at the opening to be asked several thousand dollars for the same pieces of wood that he had given Gordon earlier in the week!

In the summer show, we also had- from the Edward James Foundation- one of the Dali Mae West Lip sofas. Sadly the friend, to whom I sold it to, had to resell it about 10 years later but thankfully it went to the Boijmans Museum in Rotterdam.

Salvador Dali, Mae West Lips Sofa, 1938, polyurethane foam coated with a red polidur coating, 43 3/8 x 72 x 32 inches (110 x 183 x 81.5 cm), Boijmans Museum Rotterdam